|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

/ Credits / Gigs / Songs |

/ Interviews |

/ Videos |

Wachtel Band |

List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

/ Credits / Gigs / Songs |

/ Interviews |

/ Videos |

Wachtel Band |

List |

|

Waddy Wachtel |

|

|

|

|

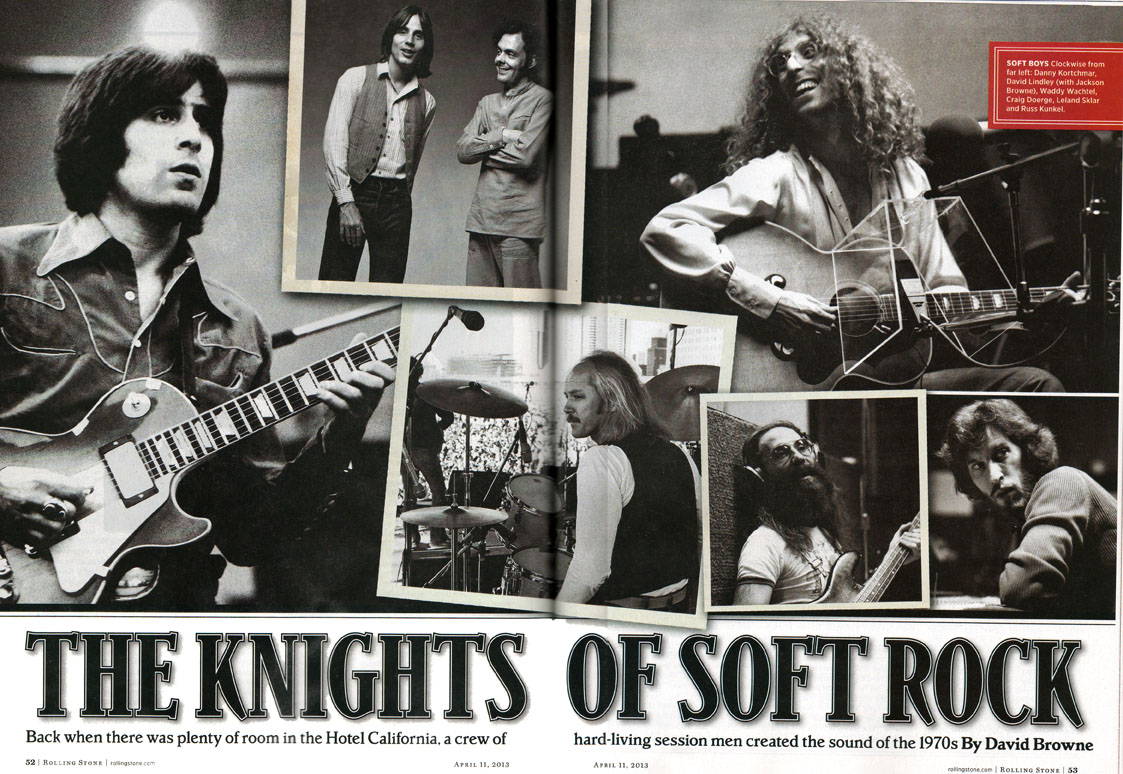

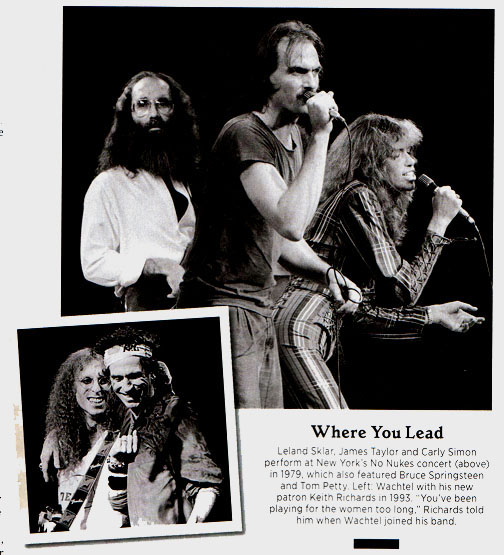

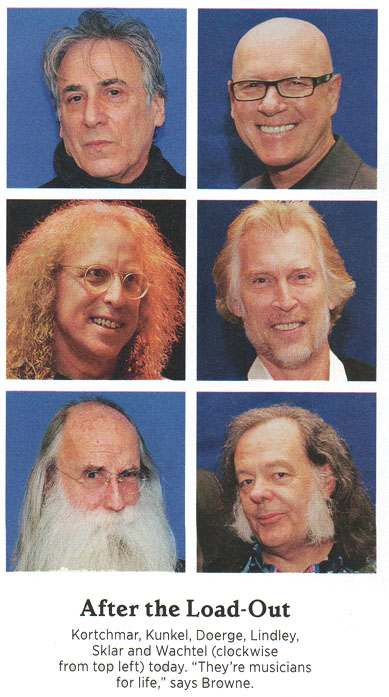

Rolling Stone Magazine April 11, 2013 The Section: Knights of Soft Rock Back when there was plenty of room in Hotel California, a crew of hard-living session men created the sound of the 1970s By David Browne  By 1979, guitarist Waddy Wachtel thought he'd seen everything. He had shown up for morning studio sessions to find Warren Zevon already wasted; he'd seen California Gov. Jerry Brown, Linda Ronstadt's then-boyfriend, retreat from a room of stoned rockers after unexpectedly popping into one of Ronstadt's sessions; he'd walked offstage after playing with Carole King and into a brawl with her boyfriend. But he wasn't quite prepared for the strange, vexing behavior of James Taylor. If anyone embodied the peaceful easy feeling of the decade, it was Taylor, whose inward-looking ballads and self-effacing stage presence hit the Seventies in its sweet spot. Women fell for the brooding guy on the cover of Sweet Baby James, men related to his reserved masculinity, and radio couldn't get enough of hits like "Handy Man" and "You've Got a Friend." But as Wachtel was learning on his first tour in Taylor's band, in 1979, another, far less relaxed Taylor lurked in the shadows. That Taylor was grappling with alcoholism and hard drugs and was in the midst of a troubled marriage to Carly Simon; their two-year-old son, Ben, had suffered from fevers in his infancy. Taylor had battled addiction before, and it was surfacing once again. The Crackup and Resurrection of Warren Zevon The hints of trouble began before the first show. Toasting the musicians and the tour at a local bar in Texas, Taylor downed two martinis in one gulp each. "I went, 'Uh-oh that's not a good sign!'" recalls Wachtel, chilling in his home studio in the San Fernando Valley. At 65, he looks very much as he did in the 1970s: like a hippie librarian, with his round glasses and slight frame. On the bus the morning after gigs, Taylor would be seen nursing the same bottle from the night before. At one gig, Wachtel broke his pinky toe after tripping over stage cables and later asked Taylor for a painkiller from his stash. Taylor begrudgingly said yes but Wachtel had to physically pry one out of Taylor's mouth when his boss wouldn't give it up. Then, one day when he was riding in the back seat of a car with Taylor, Wachtel watched as a female tollbooth clerk asked Taylor for an autograph. Looking groggy, Taylor scribbled something on a piece of paper, said, "Hi, darling, here you go," and handed it to her. Wachtel glanced over and saw what Taylor had scrawled: "You bitch, I'll kill you" signed, sardonically, "James Taylor." The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time: James Taylor Wachtel still laughs at the memory: "He was hysterical!" But in a moment of seriousness, he says, "It was pretty intense. It was tough times." For most of the Seventies, the singer-songwriter sound embodied by Taylor, Jackson Browne, King and Crosby, Stills and Nash dominated the charts and the radio, luring thousands of bell-bottomed fans to concert halls. Those acts as well as Zevon, Ronstadt and many more relied on a small, rarified group of backup musicians to shape that tight, gently rocking sound. Anyone who geeked out on liner notes back then will recognize the most prominent names: guitarist Danny Kortchmar, drummer Russell Kunkel, bassist Leland Sklar and keyboardist Craig Doerge known collectively as "the Section" plus Wachtel and stringed-instrument wizard David Lindley. One or more of them can be heard on seemingly every one of the era's defining tracks: King's "It's Too Late" and "Sweet Seasons"; Taylor's "You've Got a Friend" and his remake of "How Sweet It Is (to Be Loved by You)"; Browne's "Doctor My Eyes"; Zevon's "Werewolves of London"; Ronstadt's "Poor Poor Pitiful Me"; Joni Mitchell's "Carey"; and entire albums by Taylor (JT, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon) and Browne (Running on Empty, Hold Out). The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Jackson Browne, Running on Empty "They were the best," says David Crosby, who hired all of them as part of his and Graham Nash's band. To Crosby, who worked with the previous generation of studio players in L.A., Kortchmar and crew were a different breed: truly sensitive musicians who knew how to get inside the emotion of a song. "They weren't just playing their instruments," he says. "That was a major change. It put them one up on all the session players before them. They took it way past 'That's a B flat.'" Albums like Running on Empty set a high-water mark for skillful, soulful rock musicians. "It's one of my favorite records ever," says Dawes drummer Griffin Goldsmith, who had to learn the songs when his band backed Browne on tour. "It was so intimidating to play those songs because those tracks are incredible. It's a testament to what great players they are." To critics, Taylor, Browne, and Crosby, Stills and Nash personified everything tame about Seventies rock, and the musicians who accompanied them were inevitably guilty by association. "We were the 'Mellow Mafia,'" says Kortchmar. He recalls a particularly nasty write-up of Taylor from the time: "We had [writer] Lester Bangs threatening to stab a bottle of Ripple into James. What the fuck is he talking about? James is doing 'Fire and Rain,' 'Country Road,' about Jesus and questions and deep shit." "I can understand you have to put a label on something," says Kunkel, "but it wasn't mellow when we were playing with Warren Zevon or playing 'Running on Empty.'" As much as the people who hired them, the Section were all strong, sometimes pugnacious characters: Kortchmar was the designated rocker, almost a Laurel Canyon version of Al Pacino; Sklar's mountain-man whiskers and Kunkel's balding pate, quasi-mullet and muscular upper arms were as totemic as the music. The records they helped craft may have been laid-back, but the scene backstage was often another matter. "When I think about the drunkenness and driving home from studios in the middle of the night, it's miraculous that we're here," says Wachtel. "You could get away with a lot back then."  From the beginning, the word was "quiet." In late 1969, Kortchmar and Kunkel showed up at Peter Asher's Los Angeles house to rehearse songs for Taylor's second album. Asher, Taylor's manager and producer, didn't want the cluttered, produced sound of Taylor's flop Apple Records debut. Instead, he wanted simpler, leaner backing that wouldn't detract attention from Taylor's voice and his batch of new songs, which included an autobiographical ode to his troubles called "Fire and Rain." "The key figure was Peter Asher," Kortchmar says. "He picked us and put us together." Asher and Taylor already knew Kortchmar, a Westchester-raised aficionado of rock and blues who'd relocated to L.A. the year before. Asher also invited Kunkel, a rock drummer from Long Beach, California, who looked and sounded like an affable surfer. On piano was King, who hadn't yet launched her own post-Brill Building career and was mostly writing songs and jamming with other musicians. In Asher's empty living room, the musicians began playing Taylor's tunes. Asher didn't want to disturb the neighbors, so Kunkel played with brushes rather than sticks, and Kortchmar played softly. The result was, as Kortchmar recalls, "sensitive but meaningful accompaniment" an ideal fit for Taylor's understated guitar playing and singing. The same crew soon entered the studio and, in a few productive days, cut Sweet Baby James. The album connected with an audience still reeling from Altamont, Manson and other end-of-the-Sixties buzzkills. Kunkel heard about Taylor's breakthrough when he stopped by Asher's home office: "Peter's secretary and everyone is freaking out and going crazy," Kunkel says. "They said, '"Fire and Rain" just went to Number One!' Then you heard it on the radio forever." The invasion of the unplugged, soul-baring singer-songwriter had begun, and Kunkel and Kortchmar were immediately along for the ride. Both played on King's 1971 smash, Tapestry, the next major milestone. "We knew these guys would come in, roll up their sleeves, listen to a song a couple of times and start playing," says King, who'd been in an earlier band, the City, with Kortchmar. "We'd be recording by the third rundown." Women Who Rock: Carole King's Tapestry Defines the Singer-Songwriter Movement Kortchmar's terse guitar riffs, inspired by his hero Steve Cropper, nudged their way into the songs. He had his own rules: "The parts gotta be simple. You gotta help the song. Don't step on the singer." Kunkel became known not just for his firm, unobtrusive playing but as one of the few drummers who would read the words to a song before recording. "I'd get a feel for what the artist was trying to portray," he says. "If it's a love story and doesn't require big drums, what can I do to complete the story?" "They weren't the old, crusty studio players who'd come in and say, 'I'm here for three hours leave me alone,'" says engineer Bill Halverson, who worked with some of them on various albums. The musicians also benefited from Asher listing their names in album credits not business as usual for rock session players before that. "That made a tremendous difference," Kortchmar says. "Everybody who bought the records knew who played on them, and they said, 'Oh, let's get those guys.'" One downside: Kortchmar was listed on the back of Sweet Baby James as "Danny Kootch," after a childhood nickname "I never wanted to be Danny Kootch. I always thought it was the stupidest fucking nickname in the world." But the tag stuck. When Taylor took to the road, another player joined up a Cal State Northridge music student named Leland Sklar whose fluid bass style fit perfectly with Taylor's songs. The quartet that came to be known as the Section name chosen by Taylor, after "rhythm section" was finalized when Cleveland-bred pianist Doerge (rhymes with Fergie) was recruited to replace King. During this time, Sklar and Kunkel were hired for another session, backing a much-talked-about Orange County songwriter named Jackson Browne, who knew how to network. Doerge remembers walking up and down Hollywood Boulevard with Browne, past clubs and tattoo parlors where everyone seemed to remember Browne from the 8-by-10 publicity photos he would hand out. Kunkel and Sklar soon found themselves back on the radio when "Doctor My Eyes" featuring Kunkel's congas and drums and Sklar's burbling bass line became Browne's first hit. Browne had originally wanted to play piano himself on several songs on his debut album, including "Rock Me on the Water," but he hired Doerge when he realized he wasn't getting the right feel on his own. "That was a pivotal moment for me," says Browne. "Craig played great piano and classed up my piano playing. They removed all the impediments." During those pre-superstardom days, the scene was still cozy and informal. King brought her children to the sessions for Tapestry. At the Troubadour in L.A. in 1971, Kunkel was recruited to back another new addition to the balladeer crowd, Carly Simon. Simon knew of Taylor years before on Martha's Vineyard, but it was Kunkel who broke the news to Simon that Taylor was in the audience. "You didn't just tell me that," Simon said, blanching. Recalling the incident, Kunkel says, "That was a faux pas on my part. I had no idea of her unbelievable shyness and nervousness." After the show, Simon and Taylor met backstage, and Sklar cracked to Kortchmar, "Mrs. Taylor." He was right: Simon and Taylor would marry the following year. For Taylor's 1972 album One Man Dog, the Section congregated on Taylor's property on the Vineyard. Between breaks, Taylor showed off his pet pig, Mona, and in the distance Doerge heard Simon working on a new song. "It was 'You're So Vain,' but she didn't have the words yet we heard, 'It's a vein,'" Doerge says with a chuckle. "You could hear her experimenting on the piano with it. At the time, I'm sure all the guys were thinking, 'Well, James is the big cheese here.'" For all of Kortchmar and crew's justifiable issues with the "mellow" tag, there were times that the music could be too gentle, even for the guys in the band. During his early tours, Taylor performed sitting in a specially made wooden chair. Kortchmar would needle his boss, "You look like an old man come on, stand up!" But Taylor didn't just sit down because it was folksy he often really needed a seat: The overwhelming success of Sweet Baby James and its successor, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon, had thrown him even further off his axis. Fans were coming backstage to ask Taylor, who'd spent time under psychiatric care, for advice on their own mental issues, but as Kortchmar recalls, Taylor himself was "barely getting through the day." He turned to self-medicating: "I was just totally abusing myself all the time," Taylor has said of those early tours. "I was taking a lot of drugs." Before one Chicago show, Asher had to look for a doctor to prescribe methadone to make sure Taylor made it to the show. "We didn't know from gig to gig what was going to happen next," says Kortchmar. "We were all hanging on by our fingernails hoping everything would be all right." Kortchmar and the band had no choice but to follow Taylor's lead and sit down onstage. "I hated the sitting period," Sklar says. "We're up there like a bunch of old farts." Asher credits the band with saving the tour: "If James was under the influence, they'd find a way to fix it," he says. "They were capable of covering for him. That band owes James a lot, but he owes that band a lot." Taylor wouldn't start standing onstage until 1975, when he had temporarily gotten his drug problem under control. Given the license, the Section could let loose onstage. In 1975, Kortchmar, Kunkel, Doerge and David Lindley a California-born boho with an impish wit whose fiddle and guitar were prominent parts of Browne's sound were hired as Crosby and Nash's backup band. Crosby pushed them in ways few of their other employers did, particularly on an extended, spacey version of CSNY's "Dιjΰ Vu" that became a highlight of their live shows. "I told everybody, 'Let's get weird,'" says Crosby. "They said, 'Oh, really?'" Kunkel started the musical craziness by dropping a bunch of coins onto his drums for a clattering sound. Kortchmar and Lindley began making animal noises on their guitars, before Sklar stomped in with his bass; eventually, Crosby began playing the song's recognizable opening lick. "They were some of the most creative musicians around," Crosby recalls. "You never had to tell them what to play. You sang them a song and got the fuck out of the way." The musical adventures didn't always have such happy results. John Lennon hired Kortchmar to play on Harry Nilsson's infamous 1974 album Pussy Cats, which Lennon was producing. During one night of heavy partying at L.A.'s Record Plant, Lennon and his on-again, off-again friend Paul McCartney led everyone in a long jam on rock & roll classics. Eager to join in, Nilsson began screaming along to early-rock classics, according to Kortchmar and, as Kortchmar watched, ruined his vocal cords forever. In a Sunset Strip restaurant one day, Crosby was approached by a scrawny, bespectacled guitarist who wanted to pick his brain. Robert "Waddy" Wachtel was born in New York and, like Kortchmar, had the accent and street-savvy attitude to prove it. With his own band, Wachtel dubbed "Waddy" by a childhood friend relocated to the West Coast in the late Sixties and worked his way into the studio scene after his band fell apart. Wachtel met some of the Section at a session for Rocky Horror Picture Show star Tim Curry, and was soon assimilated into the scene despite his initial jealousy of Kortchmar. "I remember seeing Danny's name on all the records," says Wachtel. "'Who is this guy Kootch? I hate this guy!'" But the two hit it off, and Wachtel worked with most of the Section on King's 1976 album Thoroughbred. Of all their bosses at the time, King had the most strongly held opinions about recording and knew how to communicate them in the predominantly male-driven world of pop in the Seventies. "Carole knew exactly what she wanted," Kunkel recalls. "If she didn't like what you were doing, she would tell you what to play." But like Taylor and Browne, whose wife, Phyllis, committed suicide during the making of The Pretender King's personal life was complicated. On the road with King, the band had to spend time with her then-boyfriend, Rick Evers, a strapping hunk who'd served time in jail for forgery and was known for his very short fuse. Recalls Wachtel, still sounding perplexed decades later, "I thought, 'This is your boyfriend? Tall, rugged cowboy guy, dungaree shirt, pot-smoking Carole King's boyfriend?' Didn't make sense." "Evers was a dangerous psychopath," says Kortchmar, who says that Evers was jealous of the band and also nursing a serious drug habit. After an encore in the Midwest, Kortchmar was coming offstage and exclaimed, "That was fuckin' great!" and was promptly punched out cold by Evers. "He clocked me when I wasn't looking," says Kortchmar. Wachtel and Kunkel jumped Evers, punishing him until they were pulled off by others in the crew. Onstage at her piano, waiting for the musicians to join her for another encore, King heard the commotion but was unaware of the brawl. "We were ready to kill this piece of shit," Sklar says, still wincing at the memory. "I love Carole dearly, but I've had issues with some of the men in her life." Once things settled down backstage, the band threatened to bail on the tour but ultimately stayed as a show of support for King (and to honor contracts). Looking back, King said, "I learned that their character is as good as their musicianship." (Evers and King married the following year, but he died soon after from a drug overdose.) As for the Mellow Mafia, their bond was fully cemented that night. Once he'd woken up, Kortchmar looked fiercely at Wachtel and said, "Man, I just want you to know from now on, you and me: brothers forever!" As the decade wore on and the California-rock sound took over the country, the Mellow Mafia would do three or four sessions a day, bumping into one another at different studios and around Los Angeles. They were well paid, making double scale $242 for three-hour blocks (thousands of dollars a day in today's money). For overdubbing a biting lead-guitar part onto Ronstadt's "Hurt So Bad," Kortchmar earned a cash bonus of $5,000, hand-delivered in a guitar case to his home. And as the Section, Kortchmar, Kunkel, Sklar and Doerge cut three instrumental, fusion-geared albums of their own for Warner Bros. and Capitol. Like their bosses, the backup players reveled in the spoils of the time. During their tenure backing Crosby and Nash, the Section were briefly rechristened the Mighty Jitters, for not-too-subtle coke-related reasons. "That band was really, really, really high all the time," Kortchmar says with a laugh. "We were extremely jittery. Afterparties? They hadn't invented that expression. Before and during party!" During this period, the excesses rarely interfered with the work. In the studio, Wachtel laid down his solo for "Werewolves of London" in one take, before he'd even had a chance to partake of the bump of coke and drink he'd placed in front of him. The high point, with or without pharmaceuticals, was 1977. Early that year, they reconvened with Taylor to cut one of his biggest-selling albums, JT. It was Kortchmar who came up with the idea of playing a sexy, slow-grind version of Jimmy Jones' bouncy 1960 hit "Handy Man," which became the album's first smash, despite Taylor's initial reluctance to cut another remake after "How Sweet It Is." The Section had rarely played tighter and even tougher, transforming "Your Smiling Face" into a playful R&B vamp. "James playing that song by himself didn't sound anything like the record," Kunkel says. "James' songs are melodic and rhythmic to a degree. But that's not rhythmic." On the same album, Kortchmar's sinister, quivering guitar bolstered Taylor's tale of caddish behavior, "I Was Only Telling a Lie." Val Garay, a recording engineer who worked on Taylor's albums, says he dubbed Kortchmar "Switchblade": "James was never a rock singer, but it was the juxtaposition, like the way Lennon gave McCartney an edge." They'd barely had time to rest from the JT tour when, a few weeks later, they packed their bags and instruments and boarded buses once more. For the first time, they would be touring with Browne, who decided to try something fairly new: Record each show for a live album of entirely new material. Browne knew he needed the best players to pull it off, and at Lindley's strong urging, he hired Kortchmar, Kunkel, Sklar and Doerge. They weren't cheap "Up until then, I couldn't afford to tour with those guys," Browne says and to seal the deal, he offered to have them open each show with a set of their own music. "I hired them as an opening act as a way of getting them on the tour," Browne says. "It was a good decision, but it began as a strategy." Although it lasted only three weeks, what became known as the Running on Empty tour took full advantage of Browne's status, and the peak of the singer-songwriter moment. Browne recorded songs on buses and in hotel rooms (renting out the adjacent rooms so as not to irk the other guests). Doerge was able to bring his concert grand piano to every stop, in its own truck, rather than rent one for each gig. The contract rider called for plenty of Metaxa brandy, which led to Lindley and Doerge having a contest to see if they could play better drunk or straight. Lindley recalls Browne lining up wine bottles onstage and, in one possibly inebriated moment, taking off his pants onstage at an audience member's request. "Everyone thinks Jackson was Mr. Sedate," Lindley says. "He was always in control, except for a couple of times. Like once when he was walking a high wire but on the edge of the piano. It was nuts." (Admits Browne, "There was a little bit of a party vibe.") Late one night, Browne and Lindley cut a version of Rev. Gary Davis' "Cocaine," complete with the sound of Browne snorting up. Lindley, who like Sklar avoided drugs, had his own quirks. To keep hotel maids away, he'd execute a flawless imitation of a barking Doberman, down to throwing himself up against the door for added mad-dog effect. "He'd start doing that on the other side of the door, really loud, and you'd see cleaning women running down the hallway for fear of being eaten," says Crosby. Sklar's beard and affable manner disguised a sarcastic, cynical sense of humor and an impatience with his peers' drug abuse, and also with what he calls a "level of hippie incompetence" on the Browne tour, like the time a replacement for a blown bass speaker didn't arrive for a show. "I was furious and yelling and throwing shit I went berserk," says Sklar. "I probably should have taken an anger-management class." Says Asher, "If you see Lee lose his temper, it's a sight." And just as on Taylor tours, plenty of female fans showed up to see Browne's shows. Doerge and Sklar, both married at the time (and still wed to the same women), had to stick with flirting, but other band and crew members availed themselves. "We did OK," Kortchmar says, but adds, "There were tons of groupies, but they weren't all that good-looking. Hard-rock bands did a lot better in terms of women throwing themselves at you. Our fans were a little more cerebral." Despite the excesses, the Mellow Mafia always hit their marks onstage. "Danny would do some outrageous shit, like walking back and forth like a professional wrestler and pointing to himself, like, 'Check this out!'" Browne says with a laugh. After three encores at a show in Maryland, they'd run out of material, and Browne was about to go out one more time to play a song by himself. Instead, Kunkel suggested they play a song that Browne had just written: a paean to the road crew called "The Load-Out," which the musicians had discussed but hadn't worked out. They returned to their instruments and, before a packed house, gave it a shot and played it (and a version of the Zodiacs' 1960 hit "Stay") so perfectly that both wound up on the finished album. (So did Kortchmar's moving "Shaky Town," a song he'd written about a touring musician.) With the Section's help, the experiment paid off: Running on Empty hit Number Three on the album charts, and became a landmark record of the era. "The Section playing with Jackson," says Kunkel proudly, "is by far the best Jackson's ever sounded live." It had been a physically draining year and decade and Doerge's wife, singer-songwriter Judy Henske, witnessed the results firsthand when an emaciated Doerge returned home from the tour. "Judy started crying when she saw me," he recalls. "We were burning the candle at both ends." Meanwhile, Wachtel had learned that Keith Richards, of all unlikely people, was a fan of Zevon's Excitable Boy, which Wachtel co-produced and on which he played lead guitar. The praise was confirmed when Wachtel flew to a Stones show in Arizona with Ronstadt, who had hired Wachtel as her lead guitarist. Backstage, Wachtel was complimented and hugged by Richards and Ron Wood. "It was quite a moment," he remembers. "I couldn't believe it." Says Kunkel, "We thought it would go on forever." By then, punk and disco had arrived, and some of the scene's major players got a dose of pop's new world order one night in June 1978. Asher secured tickets for himself, Ronstadt, Kortchmar, Kunkel and others to see Elvis Costello and the Attractions at Hollywood High. Kortchmar had already become a fan of punk and New Wave thanks to his new, younger girlfriend, Louise Goffin daughter of Carole King and Gerry Goffin. (King had "no problem at all" with the relationship, Kortchmar insists.) Kortchmar says he loved Costello's show, but others, he says, weren't as thrilled: "A lot of people saw it as a threat. Which it was." Almost overnight, the technical expertise embodied by the Section where any note that wasn't polished to perfection was banished from the studio was passι, and the musicians were typecast. "We all had a passion for what you'd call hard rock," says Sklar, who had played in a rock band, Wolfgang, before meeting Taylor, "but then I'd get called for an album project, but only for the ballads. We got cubbyholed. You created your own monster with this stuff." Before too long, everyone was struggling to adjust to the altered musical landscape. Kortchmar and Ronstadt chopped off their long locks in favor of shorter, semipunky hairdos. After cutting one Costello song in 1978, Ronstadt decided to make an entire New Wave-influenced album, 1980's Mad Love. Wachtel was the first to quit. "At that point, I decided, 'I'm not into this music,'" he says, still frowning. "I didn't dig it. And for Linda to do this stuff seemed weird to me." Kortchmar, who'd been chafing at playing restrained guitar parts for years, couldn't have been happier at the arrival of punk. He was feeling increasingly estranged from Taylor, thanks to his boss's deepening drug use. After one last tour with Taylor, he quit Taylor's band, joined up with Ronstadt's group for her Mad Love tour, and even cut a pogo-beat solo album, Innuendo. "People said, 'What are you trying to do, jump on the bandwagon?'" Kortchmar says. "And I said, 'You're fucking right I am!' I was tired of wearing bell-bottoms. I liked skinny ties and hipster jackets. I didn't want to be a stodgy shithead. Fuck the Seventies." The excesses of the era were starting to catch up with everyone, including the Section members. While cutting Taylor's 1979 album Flag, Kortchmar who was already starting to play too fast, thanks to coke use showed up at one session so wasted that Asher sent him home. After a Ronstadt show in L.A., Wachtel drove straight to a Bob Weir session. From his drinking, he was already seeing double on the drive to the Valley, and the pile of cocaine and cigarettes at the studio didn't help. On the way home, Wachtel crashed his Volvo on the Ventura Freeway; amazingly, he wasn't seriously injured. To the musicians' continual amazement, Taylor never gave a bad performance or forgot a single lyric during this period, despite his heavy drinking. (Taylor, who is in the midst of recording a new album, declined comment for this story.) The same wasn't true for some of their other employers. Dating back to their period in the Everly Brothers band in the early Seventies, Wachtel knew Zevon was an alcoholic. But then came the night in March 1978 when Zevon played before a crowd full of industry bigwigs, not to mention Bruce Springsteen, at the New York club Trax. Zevon and Wachtel both hit the stage plastered Wachtel says Stolichnaya was sponsoring the tour, which didn't help. As Zevon began ranting and raving uncontrollably between songs, Wachtel sat down onstage and looked at Springsteen, seated in the front row. "Nice pacing, ain't it?" he told Springsteen. The all-important New York Times review called Zevon "pretty sloppy." Says Wachtel, "It was horrible. We were gross." Off the road, Doerge was dealing with the deteriorating David Crosby. Only a few years before, Crosby was an animated presence, eagerly grabbing his guitar and joining in with the band during rehearsals. But by 1979, Crosby was deep into freebase, which Doerge and Sklar witnessed firsthand when Crosby recorded a solo album with them. During the sessions, Crosby rarely emerged from his own private space. "David was on the other side of the glass in a smoke-filled room that smelled like a cat box that hadn't been emptied for eight months," says Sklar with a sigh. "He never came out." (The album was eventually shelved.) Despite his state at the time, Crosby still recalls the support he received from these players during that difficult period. "I was just completely psychotic on drugs, and they tried to keep me making good music," he says. "They tried to keep me from going down the tubes. They were compassionate." The most alarming moment came when Crosby set his freebase pipe on a studio baffle during a jam session. When he accidentally bumped into the baffle, the pipe tipped over and fell. As the musicians watched, Crosby put down his guitar and dropped to the floor in search of his beloved paraphernalia. "It was like throwing cold water over everyone in the room," Doerge says. "There was nothing David liked to do more than play. So for him to stop during a good jam we were chilled by it. We knew the party was over." 'Here's a tune of mine that Jackson Browne recorded," says Kortchmar before strumming "Shaky Town." It's a midwinter night a few months ago, and he and occasional touring mate Jeff Pevar, another longtime session guitarist, are gigging at a small club on New York's Lower East Side. At 66, Kortchmar is stockier but still has the strutting stage moves of his youth. ("Danny could get a little over the top sometimes," says keyboardist Clarence McDonald, who played with Taylor's band in the Seventies. "We had to remind him it was the James Taylor show. He had a tendency to forget.") After playing "Honey Don't Leave L.A.," a Kortchmar original that Taylor recorded on JT, Kortchmar says, "I was trying to be sensitive. We were all trying to be sensitive back then." To chuckles from the crowd, he relates a story of falling in love with a beautiful woman backstage during his time in Ronstadt's band which was only a problem because, he says, "I was living with someone at the time." Before the show, Kortchmar talks about the TV series Nashville, which co-stars his longtime friend JD Souther. "I don't think Nashville is that realistic," he scoffs. "Where's the blow? It's like that Cameron Crowe movie [Almost Famous]. How can you do a movie about that period and not show all the dope?" For Kortchmar and crew, the years of blow are also long gone, as is the Section. By the early Eighties, they'd mostly splintered. Lindley left Browne's band, at Browne's urging, and began playing his own blend of reggae, rock, blues and world music. Wachtel returned to session work that's his guitar on two 1981 hits, Kim Carnes' "Bette Davis Eyes" and Stevie Nicks' "Edge of Seventeen." Kortchmar hit rock-bottom; he was fired by a business manager and recalls passing on buying a piece of cheese in a market because it cost too much. Sklar and Kunkel continued playing with Taylor, who cleaned up during that time. An awkward period ensued when Kunkel began dating Simon, who'd split with Taylor in the early Eighties. "It was a bit uncomfortable," Kunkel admits. "A little bit difficult. But we got through it." When Simon dropped by to visit Kunkel at a Taylor show, Asher had to scramble to make sure Taylor and Simon didn't cross paths. The musicians still worked together in various combinations Kortchmar, Doerge and Kunkel contributed to Browne's Hold Out and Lawyers in Love albums, and Kortchmar co-wrote "Somebody's Baby." But an era had clearly ended. Kunkel remains philosophical about the collapse of this period. "Here's the thing," he says. "Someone like James can't reinvent himself from summer to summer. He's still going to go out there and play the same 10 songs he has to play every show, no matter what. So in order to keep it fresh, there are only a few things he can change like the musicians even when things are going well. Even Bruce Springsteen had to go out and play solo for a while." During the Eighties and Nineties, the members of the Mellow Mafia gradually found second acts. Kortchmar hooked up with Don Henley and played a large role in Henley's post-Eagles solo albums, writing, co-writing and producing tracks like "Dirty Laundry" and "All She Wants to Do Is Dance." (He tells the story of a manager who'd passed on working with him before the Henley hit, cackling, "Bad mistake on that guy's part!") Sklar joined Phil Collins' band and started getting recognized on the street thanks to his appearances in the "Sussudio" video. (When Sklar returned from a Collins stint, expecting to rejoin Taylor's band, he learned to his shock and surprise that Taylor had replaced him.) Wachtel, always a rocker ready to break out, became an integral part of Keith Richards' X-Pensive Winos ("Keith said, 'You've been playing for the women too long'"); Doerge toured with Simon and Garfunkel and then with Garfunkel alone. These days, the work continues, even if it isn't always as high-profile as it once was. With his own band, Kortchmar, now based in Connecticut, gigs around the Northeast and still gets royalties from his songs covered by Taylor, Henley and Browne. "The L.A. scene, at least the part I was involved with, is gone," he says. "Like in that Dave Grohl documentary [Sound City] that's what we all miss." In the past decade, Lindley has reunited with Browne for shows here and overseas, cutting a live album in the process. Doerge writes and records with Henske, a longtime singer-songwriter with a deep voice and a cult following. Wachtel who continues to earn royalties for co-writing Zevon's "Werewolves of London," which was used in Kid Rock's massive "All Summer Long" remains Nicks' musical director. He has also contributed guitar parts to Richards' in-progress solo album and scored movies like Paul Blart: Mall Cop and Joe Dirt. Kunkel is Lyle Lovett's drummer, and Sklar, whose trademark whiskers are now largely snow-white, keeps busy with sessions (Vince Gill next) and soundtracks, including the upcoming Muppets and Superman sequels. Says Browne admiringly, "They're musicians for life. They're not running for rock star." For the people who remember, the Mellow Mafia stand as one of the most important backing crews in pop. "They collectively changed the face of music," says Asher. "They helped in the process of taking singer-songwriters seriously. James is considered an American treasure, and they were invaluable aides to him on that journey." They may also be the last of the great session crews, before home studios, Pro Tools and GarageBand made studio ensembles superfluous. With them, a style of pop and of making records came to an end. "I'm running around with a baton in front of me and there's no one to hand it to," says Sklar. Asked to name their successors, producer Rick Rubin who occasionally uses a small, hand-picked combo when recording with acts like Adele and the Dixie Chicks pauses. "I'm not sure," he says. "You don't really need bands anymore." Kortchmar, Kunkel, Wachtel and Sklar have been approached about participating in a rock & roll fantasy camp devoted to rhythm sections. "If one of your ambitions is to hang out with Sammy Hagar, you'll be disappointed with us," Kortchmar says. "But we want to demonstrate what it's like to play in an ensemble. That isn't taught much by anyone." The Mellow Mafia players received vindication of sorts three years ago, when Kunkel, Kortchmar and Sklar toured once more with Taylor and King. With its wall-to-wall set list of singer-songwriter classics from the era, the arena tour grossed more than $63 million. For the musicians, the shows were more than a first-rate payday. "When we did that tour, so many people came up to us and said, 'Now, that's how that stuff is supposed to sound,'" says Kunkel. "I'm sure James' current band didn't like to hear that." He pauses but only briefly. "But too fucking bad. I'll quote Danny Kortchmar: 'Some things are better than others.'"  | Modern Recording and Music | Guitar World | Guitar Player | International Musician | Musician | Misc. Articles | Waddy Wachtel Interview Part 1 | Waddy Wachtel Interview Part 2 | Nina 1 | The Record | Bam Magazine | WW Book References | Keith Richards Life | L.A. Magazine | Soundcheck | Rolling Stone Magazine 4/11/13 | Burst Believers | WW Interview by Joe Bosso | WWGibsonInterview11/28/14 | WaddyWachtelInterview12/18/14 | | Return Home | Discography / Credits / Gigs / Songs | Articles / Interviews | Photos / Videos | Contact | Waddy Wachtel Band | Search | Mailing List | |

||

|

|